The Lewis County Almshouse

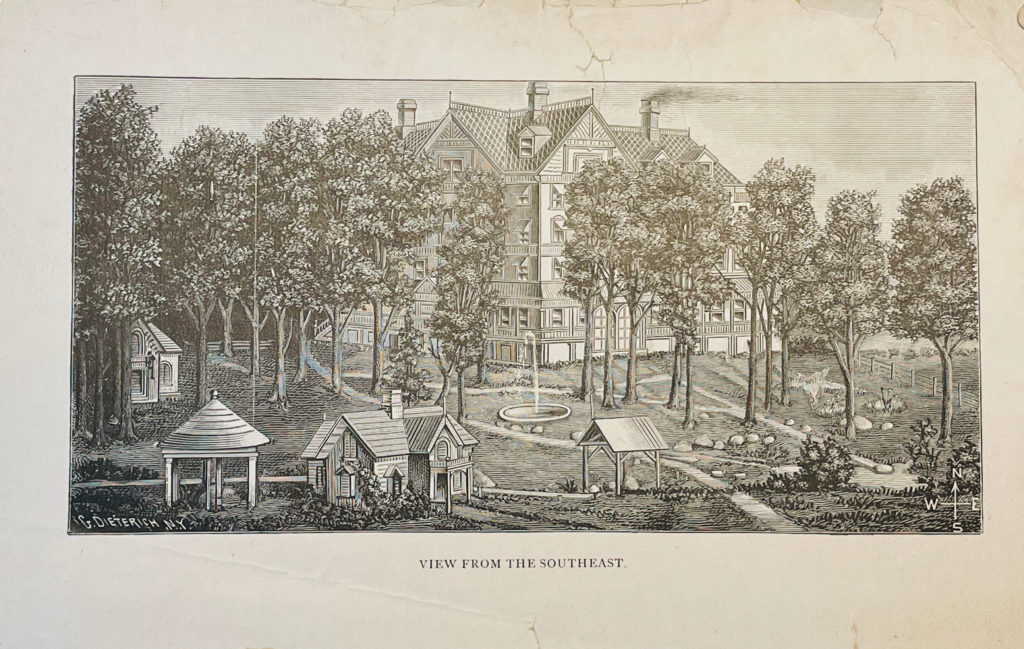

Just outside Lowville on outer Stowe Street used to stand one of Lewis County’s great old historic buildings, or set of buildings, now unfortunately long gone: the Lewis County Almshouse (or Poorhouse) – or what in later years came to be called the “County Home.”

In 1824, New York passed the County Poorhouse Act, which was designed to help disadvantaged citizens by authorizing county governments to open houses to place and take care of people that were unable to care for themselves, including the poor, elderly, sick, and disabled. As a result, almshouses began to pop up all over the state. They were funded by taxpayers and managed by county governments, thus alleviating local towns of the responsibility for the poor that they had born prior to the 1824 Act. At the time, Lewis County was ranked 46th in the state for pauperism.

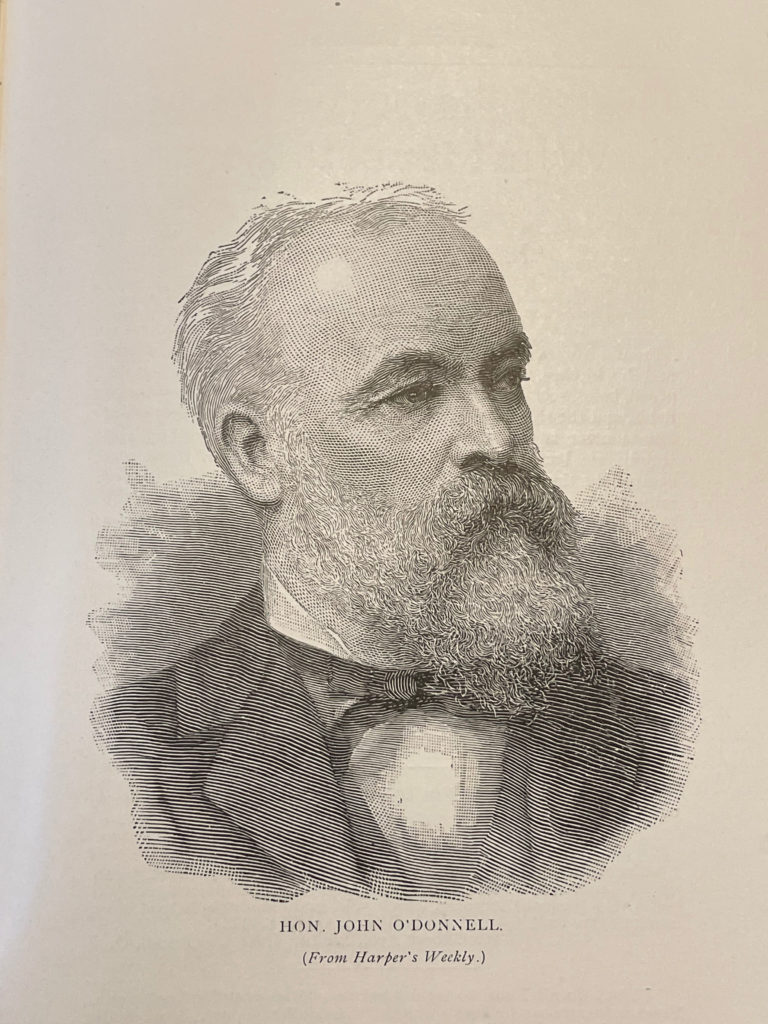

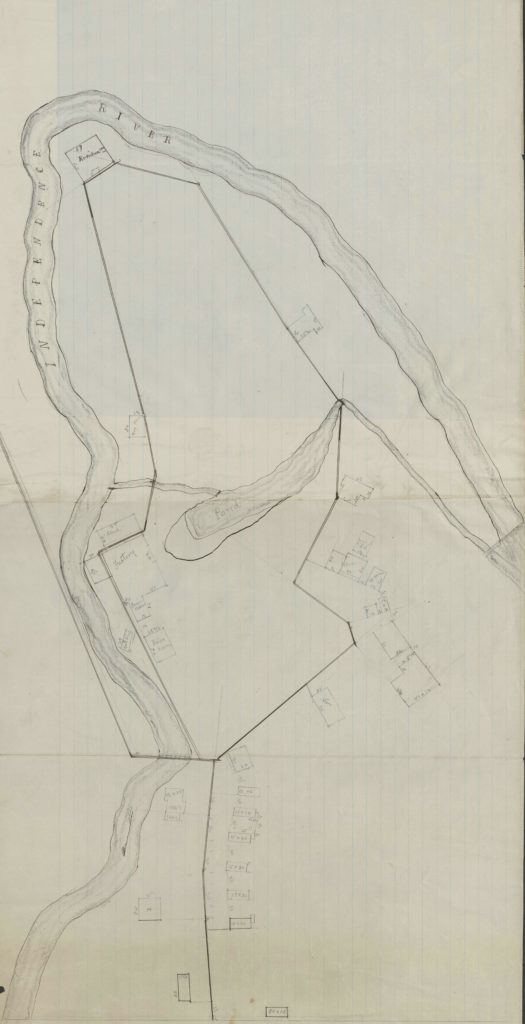

As a result, some of Lewis County’s most distinguished and respected men at the time, Judge Jonathan Collins, Charles Morse, and Stephen Hart, were given responsibility for finding a suitable location to erect a county almshouse, which they promptly did – choosing the former farm of Major David Cobb, some 60-acres located just west of Lowville. Initially, the Cobb family farmhouse and buildings were repurposed for use as the first Lewis County Almshouse.

A Superintendent of the Poor was appointed to be responsible for managing the social welfare of the county’s impoverished. Some of the first appointed officials to occupy the role were men of distinction: Judge Nathaniel Merriam (one of the county’s earliest county judges and patriarch of Leyden’s Merriam family); Philo Rockwell (Gen. Walter Martin’s son-in-law); Stephen Leonard (prominent Lowville businessman); and Paul Abbott (merchant tailor and builder of Lowville’s 1812 House).

Judge Jonathan Collins

The Superintendent, in turn, would appoint the Keeper of the Almshouse, and the Keeper and his wife (often called Matron of the House) would both live and work at the facility, although as time passed a separate brick house was later built for them further down Stowe Street. The Keeper and his wife were responsible for running the Almshouse and attending to the safety and comfort of its residents. They would manage the grounds, including the 60 acre farm, supervise the residents while they worked, and help supply all resources needed by those at the facility, like food and medicine. The first Keeper of the House on record was Samuel S. Raine of Lowville.

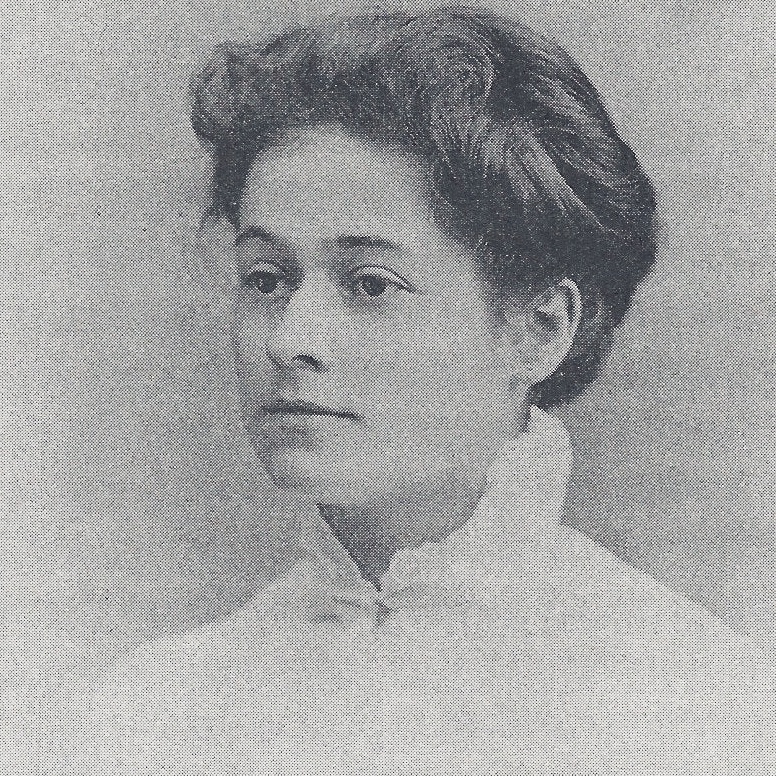

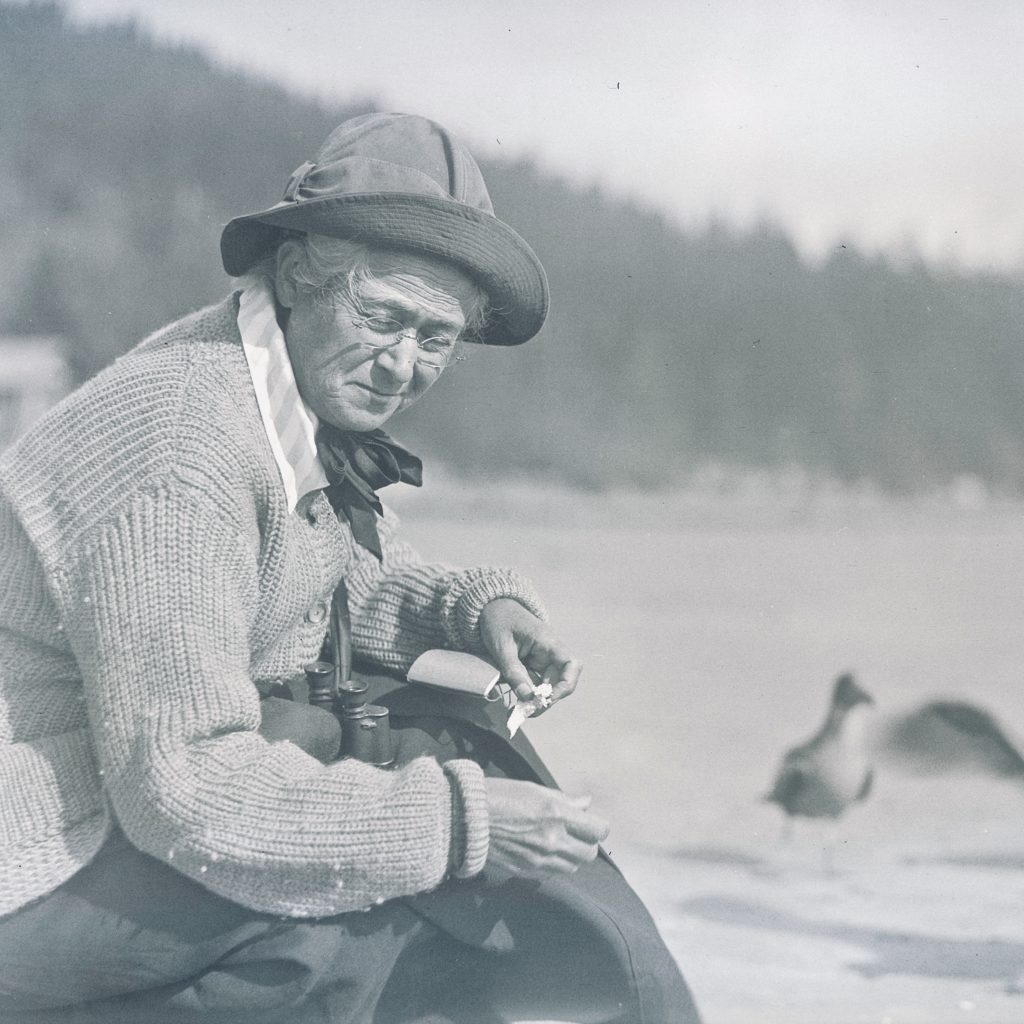

This County Home facility went through several renovations over time, the first of which was prompted by a visit from Dorothea Dix, the 19th century social reform advocate for the indigent and mentally ill. Dix traveled all across the eastern United States, visiting poorhouses, jails, and asylums and kept a detailed record of her visits in a journal. In 1844, she toured Upstate New York, where she found the conditions of the Lewis County Almshouse to be poor, primarily because she found the size of the facility too small and smell of the place disagreeable. However, she did believe that the Keepers of the House did the best they could for what they had, and thought the residents were generally treated well. These remarks were a welcomed relief to the alternative, as Dix was well-known for exposing any abuse happening at an almshouse, which often was the unfortunate case at other locations in the state. Still, it was clear that reform was needed in order to comfortably accommodate the increasing numbers of people that were seeking relief in Lewis County. To that end, Dix, who was also a philanthropist, donated some of her own wealth towards the efforts of a new and improved County Home.

Dorothea Dix

A two-story limestone building, 40 by 60 feet, was promptly erected on the property, which improved conditions dramatically. The needs of the County’s impoverished and mentally ill continued to grow, however, and within 25 years, even more space was required. By the late 1860s, the stone building had been replaced by a much larger, quite magnificent three-story brick structure (at a construction cost at the time of $11,500), and shortly thereafter a separate two-story brick building to house “a lunatic asylum” was also erected (at a construction cost of $8,000). When control over supposed “insane” patients was later transferred to state control in the 1890s, 33 residents were relocated at the time to the state mental asylum in Ogdensburg.

By the early 1900s, the Lewis County Almshouse had its own hospital. It owned and operated its own farm, with barns and outbuildings, the proceeds of which went to help defray the costs of operating the Almshouse. And it maintained its own cemetery for the indigent, which still sits just across the street, is marked by a large white cross, and contains over 150 internments.

At its height, the Almshouse could house upwards of 100 people, and typically averaged between 30 and 60 a year. It became home to people who could not care for themselves for any number of reasons: the poor; widowed mothers; immigrants; the sick and injured; those who were deaf or blind; and those with other special needs. Those who were more able-bodied worked on the farm and performed other duties in exchange for being able to live there and receive care. Despite the negative associations that poorhouses often carry, the Almshouse was home to many people for many years; many residents spent the majority of their lives there; and a number of them are still interred on the property.

The County Home, as it came to be called, operated as an almshouse well into the 20th century, and prided itself on providing clean and comfortable relief for all who stayed there. By the 1950s, however, the county began to explore other ways to help battle poverty: the Keeper’s position was abolished in 1954; the farm’s machinery and livestock were auctioned off in 1957; and the County Home came to be used primarily as offices for the Lewis County Welfare Department by 1960. Sadly, the historic brick buildings making up the County Home complex were demolished by the county in 1986, only to be replaced by a handful of county buildings lacking the architectural and historical significance of the buildings that once stood there.