Conscience and Conflict: Lewis County Mennonites and Conscientious Objection

In the modern era, those who have served in uniform are held with a special distinction. Those who have willingly committed themselves to protecting our country throughout our nearly 250-year existence are memorialized in monuments, museums, parades, and ceremonies. If you walk into any store or restaurant it is not uncommon for someone to thank a veteran eating lunch or shopping, the veteran’s service identifiable by a ball cap, T-shirt or tattoo. But what about those who served in other ways?

Those who are restricted by religious beliefs or do not agree with a cause that is being fought for?

Dating back to the 1600s, religious groups such as the Quakers, Mennonites and Shakers held beliefs which forbade them from carrying arms in warfare. These early religious groups were the first conscientious objectors in America. The group with which most from Lewis County are familiar are the Mennonites. When the Mennonites began settling in the county in the 1800s, my family included, they quickly became a very large segment of the population. It did not take long for their status as conscientious objectors to create conflict.

During World War I, there was a sharp divide between “Progressive Mennonites” and “Plain Mennonites.” Progressive Mennonite draftees believed the tenets of their faith allowed them to serve in non-combat

support positions in the military. Plain Mennonites on the contrary maintained that under no circumstances would they consent to military service. Many military officials refused to recognize any difference between Mennonite groups or work to reach any sort of compromise. During World War I, 138 Mennonite conscientious objectors were court-martialed throughout the country, according to a 2015 report in the Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies.

During World War II, as America rallied around defeating fascism and saving the free world, Mennonite conscientious objectors in Lewis County faced harsh criticism from many but also understanding from the federal government. After the backlash faced by Mennonites during World War I, a large amount of “peace literature” was published in an attempt to explain the history of Christian peace churches, which includes Mennonites, Anabaptists and Quakers, and the reasoning behind their beliefs. Representatives from the Historic Peace Churches were at last successful in persuading President Franklin D. Roosevelt to offer alternative service, and Civilian Public Service, or CPS, was created with passage by Congress of the Selective Service and Training Act of 1940. This occurred despite opposition from many veterans organizations.

In Lowville, American Legion Post 162 in 1943 strongly opposed the law’s creation and appealed directly to officials in Washington to induct conscientious objectors into the armed forces as they argued the CPS

camps “are not contributing successfully to the military effort,” according to a resolution adopted by Legion officers in July that year. Legion officials opposed placing COs in Red Cross and other behind-the-line facilities at higher pay than soldiers and sailors and urged that COs instead be inducted into the military to fill noncombatant medical positions at equal pay with combat forces. Veterans at the Lowville post further resolved “that any further or other preferences for conscientious objectors be emphatically denied, as against the morale of our fighting men and women and a great majority of the population of these United States.”

In 1941, Sidney Schaefer, Amos Widrick, Menno Moser and Ernest Steria, my great-uncle, were the first four Lewis County Mennonites to express their beliefs as conscientious objectors during wartime and serve in the CPS.

My great-uncle Ernest, however, served only a short time in the CPS program. According to one of his eight daughters, he fell in love with a girl named Dorothy who was not Mennonite. (He and Dorothy Gadbaw were married in 1941 at the United Christian Church in West Carthage.) Expelled from his Mennonite church, Ernest lost his CO status. He left the Steria family farm on Kirschnerville Road in Croghan for Army service in April 1944. By the end of that year, he fought in the Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes Forest and earned a Purple Heart when he was wounded in the shoulder while a buddy in his foxhole was killed. Sent to a hospital, he recovered and returned to combat.

According to a family relation, Ernest after the war had to report again to his Selective Service draft board. One of the board members told him, “See, that wasn’t so bad, was it?” Ernest, who collected 10 percent monthly disability pay for his war injury for the rest of his life, lunged across the counter at the man. After that he settled in apparent peace on the dairy farm on Kirschnerville Road which he and his wife owned and operated for 34 years. At the time of his death he was a member of Croghan Mennonite

Church.

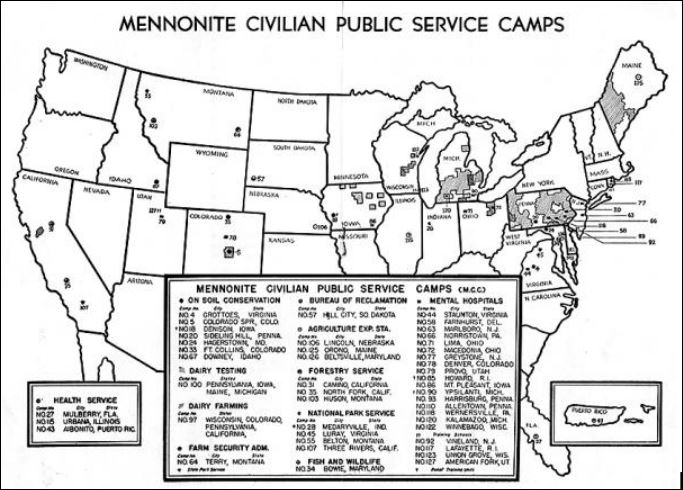

Throughout World War II, Lewis County Mennonites worked without pay in 151 CPS camps around the country. Twenty Lewis County Mennonites in all served in the CPS program during its six-year existence, some serving four years or more. Their alternative service took them to locales from Virginia to California. They worked in general hospitals and mental hospitals, on farms, in logging operations, parks and soil conservation projects.

Work in mental hospitals was particularly valuable, although taxing. One such CPS worker could no longer handle the strain from working in such a facility. After 11 months he penned an article describing the difficulties and the rewards of working at a mental hospital in Medical Lake, Washington. He wrote: “In conclusion, I would like to appeal to all C.P.S. men to seriously consider hospital work. The need is very great, and there is a satisfaction and emotional reward in directly and personally helping people in need, which can be found in no other sort of work.” It was experiences such as his by CPS workers that brought to light the challenges faced by mental hospitals and abuse of patients and directly led to changes in those facilities.

The work of these conscientious objectors, while not in combat, could be dangerous. Of the 20 Lewis County Mennonites who served, one, Arthur Lyndaker, a 31-year-old timber broker from Croghan, was killed in Janaury 1945 when a tree he was pushing over with a bulldozer broke and fell on him at a CPS camp in Hill City, South Dakota.

Many other Mennonites in Lewis County during wartime received farm deferments, which allowed them to remain on the family farm to supply the war effort.

Despite their vital efforts as farmers and work in the CPS, many Mennonites faced bitter sentiments during this time, especially from service members returning from combat who felt that they sacrificed much while others at home reaped the benefits. This trend would also continue through the Korean War in the decade after the end of World War II.

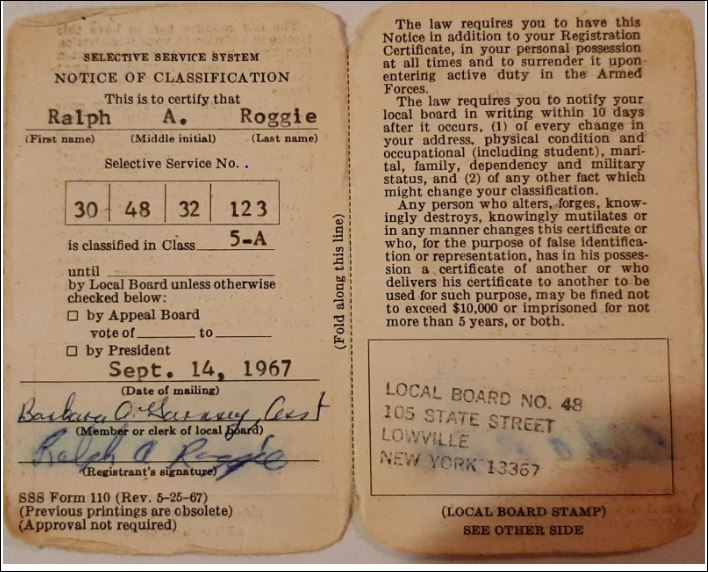

My grandfather, Ralph Roggie, was served his draft notice during that time. He arrived before the draft board in Lowville after declaring his status as a conscientious objector and requesting a deferment as a farmer. It did not take long for one board member to become angry with my grandfather’s refusal to take up arms. He promptly picked up a book, threw it at my grandfather, and told him to get out.

In 1953, the case of two Lewis County Mennonites was investigated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The men, Howard Roggie and Royal Widrick, refused to take the oath of enlistment when summoned for military induction in Syracuse. Their local draft board in Lewis County had rejected

their status as conscientious objectors.

When the Vietnam War began in the 1960s and quickly escalated, it was not only Mennonites who objected to military service. Many of us are familiar with the images of young college-age men burning their draft cards in protest of the war or have heard stories of young men fleeing to Canada to avoid conscription in the military. This was a new kind of war. Like the Korean conflict, the distant war in Southeast Asia did not stir up patriotic feelings for many Americans. The threat of Communism did seem real but the idea that Asian nations would fall like dominos to Communism if North Vietnamese Communist forces were not stopped in South Vietnam — the so-called domino theory — did not seem all that likely to some Americans. To those Americans, military engagement in Vietnam appeared more like

the U.S. interjecting itself in other countries’ affairs.

Amid the widening antiwar opposition, Mennonites and other religious groups no longer stood out in the crowd as objectors. Some Mennonites did serve in the military during this time when their draft notice came up, as did others before them in previous conflicts.

Conscientious objectors serving in the military were often put in support roles as opposed to combat. Perhaps the best-known example of such service is that of Desmond Doss, an Army combat medic during WWII who was the first conscientious objector to earn the Congressional Medal of Honor. His story was featured in the 2016 film “Hacksaw Ridge.” One local Mennonite who served in the Marine Corps during the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector was the late Larry Moser. An ambulance driver in

Vietnam, he served from 1969 to 1971 and without a doubt played a vital role in the military despite his objector status. His death in 2005 from pulmonary fibrosis might have been caused by his exposure to Agent Orange, the toxic chemical herbicide widely sprayed by U.S. forces in Vietnam.

Many other Mennonites drafted into service during the Korean and Vietnam wars were classified as I-W or 1-W. Created by an amendment to the Selective Service Act of 1948, the classification allowed conscientious objectors to commit to two years of civilian service contributing to the maintenance of national health, safety or interest, similar to the Civilian Public Service program of World War II. One local resident with whom I spoke described his I-W service to me. This individual, who wished to remain anonymous, showed a range of mixed emotions, from guilt to pride in public service, when recalling his experience as a conscientious objector 50 years ago. His 24-month civilian service took him to Vermont, where he worked on a building and grounds crew at a hospital in Burlington. He clearly enjoyed the work and was unsure about leaving Vermont to return to Lowville and his prior employment. (Employers of COs with I-W status were required to hold open those individuals’ jobs for their return, as with returning combat veterans). It was evident in our conversation that he struggled with his decision half a century ago when many of his classmates fought in Vietnam, some not returning.

My Mennonite family’s experience is a bit of an anomaly. My father Keith W. Steria served 34 years in the military between the Marine Corps and Army National Guard. During this time he traveled the world and served in many roles. Ironically, my father faced criticism and verbal taunting in the military when it was discovered that he came from a Mennonite background. One soldier even threw a full can of soda inside a tank in which my father was working as he walked by.

Republished from the 2022 Lewis County Historical Society Annual Journal

Explore More Posts

Categories

- Goings On (5)

- Objects & Artifacts (2)

- People (9)

- Places (5)

- Preservation (2)

- Uncategorized (15)